About Tofino Past & Present

n̓ačiqs (Tofino) is situated within the ḥaḥuułi (territory) of the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation. Tourism Tofino is committed to honouring these living histories and supporting their legacies.

This content was written in collaboration with Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks.

The Tla-o-qui-aht people are a Nation amongst the Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations, culturally and linguistically. Nuu-chah-nulth territory runs along the West Coast of Vancouver Island and stretches from Port Alberni, north to Nootka Island, and south to the northern tip of Washington. The Nuu-chah-nulth peoples have called these lands home for millennia.

While Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation peoples have lived here for time immemorial, the community currently includes over 1,200 citizens who reside in the ancient village sites of huupic̓atḥ - Opitsaht and hisaawist̓a – Esowista , t̓ayḥiistanis – Tyhistanis and now n̓ačiqs – Tofino. This means that past and present collide as ways of life practiced for thousands of years persist and language revitalization projects rebuild cultural knowledge.

Life along the coast was - and still is today - dependent upon the relationships that Tla-o-qui-aht Nation continues to nurture and maintain through upholding Natural Law with the practice of ʔiisaak: to observe, appreciate and act accordingly. Guests in Tla-o-qui-aht territory are requested to learn and respect these teachings by taking the ʔiisaak pledge.

The word “Nuu-chah-nulth” means the people “all along the mountains and the sea”.

Ways of life

Tla-o-qui-aht are master carvers and build and trade canoes to other Nations as they have for many generations. Nuu-chah-nulth ocean-going canoes inspired modern navy hull designs seen worldwide today. Tla-o-qui-aht continue to showcase their skills as artists, fishermen, and refined singers and dancers. Historically they are also known for their warrior discipline of protection, particularly when Tla-o-qui-aht people defended their home from American invasion in 1811. Nuu-chah-nulth Nations are also set apart from their Tribal neighbours and are known for their historical spiritual discipline of whale hunting and a continental trade in oil and shell currency.

Leaders in stewardship

Tla-o-qui-aht Nation is one of the first communities to declare Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCA) as Tribal Parks, which continues to demonstrate ecological knowledge and upholds the cultural lifeways that community members practice.

Support Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks

Interested in visiting the original Tribal Park? You can access wanačas hiłḥuuʔis, Meares Island Tribal Park through stunning trails and waterways, such as the Big Tree Trail on Meares Island. View a map of Tla-o-qui-aht territory here. Or, simply turn on your tap when you visit Tofino: n̓ačiqs / Tofino’s drinking water is provided with gratitude from the territory on Meares Island stewarded by the Nation.

You can support the Tribal Park Guardians’ conservation efforts by making conscious purchases from accommodation providers, eateries, and storefronts that are Tribal Park Ally certified. This means that 1% of your purchases get returned to Tla-o-qui-aht for their Ecosystem Service Fee, which is re-invested in the people and the ecology that comprise the life of this place.

Meet the Tribal Park Allies.

Arrival of settlers

Non-native people arrived in Nuu-chah-nulth territory relatively recently compared to the long-established Tla-o-qui-aht communities. In the 1850s, Tla-o-qui-aht permitted settlers to build a trading on čačatic (known as Clayoquot Island, formerly Stubbs Island). The settlement was named Clayoquot, an anglicization of ƛaʔuukʷiʔatḥ/Tla-o-qui-aht. The site included a Japanese fishing village, all of whom were forcibly removed during World War II by the Canadian government.

In the 1900s, n̓ačiqs - the tip of the Esowista peninsula - was labelled Tofino. Historically, this was not a village site for Tla-o-qui-aht, but a lookout point to defend the village of huupic̓atḥ - Opitsaht. The name Tofino came from foreign explorers who named Clayoquot Sound’s southernmost inlet after Spanish Captain Vincente Tofino de San Miguel. Though the captain never came to this area, the name remained and evolved as the settlement grew and was populated mainly by European immigrants.

Canada's Indian Act pushed Tla-o-qui-aht citizens onto tiny Indian Reserves. The Indian Agent assured Tla-o-qui-aht leadership that the Indian Reserve delineations were just a formality and that Indigenous people's ways of life would not be affected whatsoever because Tla-o-qui-aht Territory was much too wild and unfavourable for ‘civilized’ Europeans so nobody would ever want to live here.

While much oppression and invasion happened over the next hundred years, the construction of a logging road in 1959 dramatically increased access to the Esowista Peninsula and n̓ačiqs. Before long, people charmed by the area began visiting more regularly. They camped on Tla-o-qui-aht beaches and spent time in the ocean swimming and surfing. The town of Tofino was nicknamed Tuff City while the commercial fishing industry boomed like a gold rush.

Environmental reawakening

Both residents and visitors saw the need to preserve the precious cultural environments and ecosystems of this area. One initiative helped establish Pacific Rim National Park Reserve in 1971. The following year, the logging road was paved over.

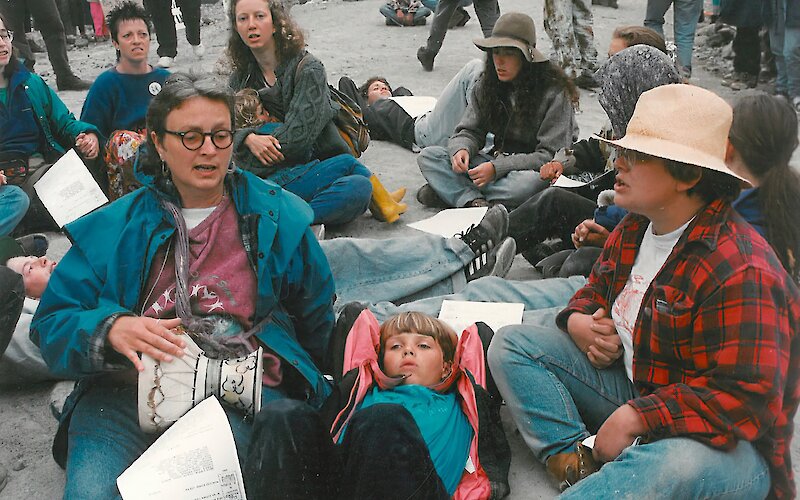

In 1979, MacMillan Bloedel, the largest forestry company in BC, announced plans to log Meares Island. A period of intense activism to protect salmon habitat and the ancestral old-growth cedar gardens followed, led by Tla-o-qui-aht, other allies, and the newly-formed environmental group Friends of Clayoquot Sound (which operates to this day). Tla-o-qui-aht traditional leadership took the Province to court in 1984 to establish protected areas where industrial forestry practices were banned. These areas are now known as Tribal Parks. In 1993, support from environmental allies to protect the old-growth forests of Clayoquot Sound from logging made international headlines and became known as the “War in the Woods”. This led to deferrals of forestry tenures, and was the largest act of civil disobedience in Canadian history until the Fairy Creek blockades on Vancouver Island. It was a tense time, as many community members still worked in the logging industry.

Present day

In 2000, Clayoquot Sound was designated as British Columbia's first UNESCO Biosphere Region. While this designation does not provide legislated protection, it provides a framework for bringing the region together through innovative education programs; community and ecosystem health research; and support for resident-led initiatives. The Clayoquot Biosphere Trust is the local organization that supports the spirit and intent of the UNESCO Biosphere designation.

In 2024, Tla-o-qui-aht and Ahousaht First Nations announced with the Province of BC, the proposed conversion of approximately 77,000 hectares of Tree Farm License 54 (TFL 54) into conservancies in the Clayoquot Sound. This was adopted and came into effect on June 26, 2024 and will mean the permanent protection of old-growth forests and critical ecosystems in these areas.

Today, Načiks (Tofino) is still a small community of approximately 2,500 residents. This town thrives and continues to evolve from its unique history. The future well-being of Načiks is dependent on healthy coastal ecosystems safeguarded by Tla-o-qui-aht Nation. Tofitians continue to support one another in preservation, conservation, and education about this incredible region we are all so lucky to call home.